Jump to updates since original publication.

The financial wellbeing of the residents of the United States is dependent upon inflation coming back under control. Current levels of inflation are driving real returns on many assets negative. This leads to diminishing real earnings and less buying power for most of the population. Purchasing power further deteriorates due to rising interest rates on debt. The Fed’s ability to tighten the money supply is directly related to their ability to fight inflation. But, how much can the Fed tighten with current monetary policy?

The impact of Fed tightening is uncomfortable in the short term. But, rampant inflation can be economically catastrophic. Most attention focuses on Fed policy to combat inflation. Price stability (lack of inflation) is one of the Fed’s mandates. The Fed has a number of monetary tools to tighten the money supply and reduce inflation. However, the Fed may not be able to tighten as much and for as long as needed. There are a number of factors constraining the Fed’s ability to tighten the money supply and reduce inflation. This article examines several constraining factors.

The Fed cannot tighten by raising rates too high for too long or it will make the US Government insolvent. How high and how long do we have?

The Government Debt Limit Calculator provides a rough visualization of when the government may reach this limit. The model assumes current interest rates and similar spending patterns. Given these assumptions, the interest payments on the debt will grow significantly. The current recent quarterly average is around 12% to 13% of receipts. In 5 years, interest payments on the debt would rise to around 30% of federal government receipts, under these assumptions. At eight years, under these same assumptions, interest on the debt will account for 50% of government receipts.

If interest rates continue to climb, interest payments will climb as well. This would result in total government receipts not covering interest on the debt prior to the eight-year mark.

While reasonable assumptions are possible, future outcomes are uncertain as they are influenced by many factors. These factors will change based upon the economy, fiscal decisions, and monetary policy. Current receipts, interest rates, and interest payment trends will lead to poor outcomes. However, changes in these factors would change the outcome.

Circumstances are unlikely to force the Fed to reverse their interest rate policy within a couple of years to maintain the solvency of the Federal Government. However, higher interest rates will lead to significant degradation in the Federal Government’s financial position over the next several years. This dynamic will exacerbate the constraint discussed next.

You can examine the numbers yourself and see how changes to certain assumption influence the outcome with the Government Debt Limit Calculator.

The Fed can not tighten indefinitely via balance sheet reduction. The government’s need for funding constrains it.

As the federal government spends more than they bring in, they must sell bonds to finance their operations. In order to sell enough bonds, there has to be sufficient buyer demand for treasuries. If private party buyer demand is lacking, the interest rates that the government would have to pay on treasuries increases. If private buyer demand is insufficient, the Fed would need to revert to buying treasuries. Or the government will have to pay excessive interest rates. This forces the Fed to make a choice. They could either continue to fight inflation through balance sheet reduction or purchase bonds to fund the government. Making the choice to purchase treasuries results in the Fed loosening rather than tightening the money supply.

This risk of finding ourselves in this either/or situation is realistic. If the Fed chooses to continue tightening in this scenario, they could keep fighting inflation. However, the Federal Government will face increased borrowing costs due to higher interest rates. Alternatively, the Fed could pivot and begin purchasing bonds again. This, which would aid the Federal Government by reducing their interest rate on debt. But, this negates the Fed’s ability to tighten via balance sheet reduction.

What factors suggest that this pivot may be on the horizon?

A) Foreign markets have been showing a reduced appetite for US Treasuries

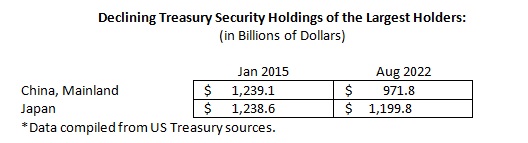

Mainland China and Japan have held the largest portfolios of US Treasuries for many years, but have begun divesting them. Both had larger portfolios of US Treasuries in January 2015 than they had as of the end of August 2022.

Similarly, overall US Treasury holdings held by foreign investors have dropped since the end of 2021. As of December 2021, foreign holdings of US Treasuries were $7,747.6 billion. As of the end of August 2022, they had shrunk to $7,509.0 billion. At the same time, total US debt has grown significantly.

There are couple of possible explanations for these declines. First, there is a greater perceived default risk of US Treasuries as US debt to GDP has continued to climb. This may reduce foreign interest in Treasuries. Second, the considerable economic problems Japan is facing may lead to reduced demand for US Treasuries by Japan.

Decreased appetite for treasuries is likely to continue

This trend of turning away from US treasuries is likely to continue or possibly accelerate for at least three reasons.

First, sanctions and asset seizures increase risk to foreign investors. The recent seizure of Russian funds shows US willingness to discard asset ownership in the face of political conflict. Ethical considerations aside, this action serves as a strong disincentive for foreign entities to hold US treasuries. A foreign entity would be foolish to invest in assets that the US seizes during a conflict. This makes treasuries a more risky investment for any entity that could potentially come into conflict with the US. After all, how valuable is an asset when it can vanish solely at the will of another party.

Second, US Treasuries are not a very appealing investment. Their yield is below the rate of inflation, thereby currently providing a negative real rate of return.

Third, a great many countries are facing their own significant economic problems. This generally negatively affects their financial situation, therefore leading to lower external investment. Hence, likely lower investment in US Treasuries.

B) Individual buyers face high inflation and rising interest costs, limiting the money available for investments

Additionally, like foreign nations, individuals receive an interest rate on US treasuries that is below the current rate of inflation. Meaning they earn a negative real rate of return. Both their capability to buy Treasuries and the attractiveness of Treasuries as an investment suggest softer demand from this segment.

C) Banks may pick up some of the slack in the US Treasury market, but not enough

Banks are buying some treasuries, but not nearly at the pace that the government is accruing debt. From the end of the 2nd quarter of 2021 to the end of the 2nd quarter 2022, the government accrued over $2 trillion in additional debt. During that same time, FDIC insured banks’ holdings of treasuries grew approximately $342 billion (see U.S. Government Debt and Banking Dashboard for details).

This means that banks purchased about one sixth of the treasuries over this period. It is unreasonable to assume that the banking sector will absorb most of the treasuries over time. Nor is it reasonable to assume that they will make up for the decrease in foreign purchasers and individual buyers. Short-term government bonds may be attractive as fear prevails and interest rates continue to rise. Long-term bonds have a negative real yield and are not truly a viable investment. This is especially true as expectations are that rates will continue to rise.

D) More US treasuries issued, but little reason to buy them

The Federal Government is creating new debt at an accelerating pace, thereby increasing the supply of US bonds. This is at precisely the point that they are an unappreciated and unprofitable investment. Federal debt created in the last three years accounts for more than a quarter of total federal debt (see U.S. Government Debt). For an illustrative look at how huge the Federal Government’s spending is (see Federal Government Spending : Big, How Big?)

Taken together, these factors create a notable risk that US Treasury rates will rise without Fed support. This threat is magnified if inflation persists longer than expected. This increases the chances of forcing the Fed to choose between fighting inflation and insuring that the Federal Government can borrow at reasonable rates. In other words, this could force the Fed to choose between tightening and loosening. Determining exactly when the Fed is forced to make this choice is difficult. But, the signs indicate the approach of the time when the Fed must choose between fighting inflation and funding the government.

Similar problems abroad

The above statement may appear sensationalized when considering the United States. But, let us examine a country that is similar in many ways and is currently experiencing a similar issue. Like many nations, the United Kingdom is experiencing a high level of inflation. Its central bank, the Bank of England (BoE), has been combating inflation by raising interest rates. On September 22, 2022, it announced that it would reduce its balance sheet by selling assets:

At its meeting ending on 21 September 2022, the MPC voted to reduce the stock of purchased UK government bonds (gilts) held in the Asset Purchase Facility (APF), financed by the issuance of central bank reserves, by £80 billion over the next twelve months, to a total of £758 billion, in line with the strategy set out in the minutes of the August MPC meeting.

Bank of England

This statement indicates tightening through bond selling (balance sheet reduction by the BoE) for the upcoming year.

Then, as recently as September 26, 2022, the BoE reiterated their policy of tightening in a press release. Saying in part:

The role of monetary policy is to ensure that demand does not get ahead of supply in a way that leads to more inflation over the medium term. As the MPC has made clear, it will make a full assessment at its next scheduled meeting of the impact on demand and inflation from the Government’s announcements, and the fall in sterling, and act accordingly. The MPC will not hesitate to change interest rates by as much as needed to return inflation to the 2% target sustainably in the medium term, in line with its remit.

Bank of England

Not only did they state that they were going to sell bonds, but also that they were prepared to continue to raise interest rates. In fact, they state that they would raise them by as much as needed. Taken together, these statements certainly point to a strong statement that monetary policy will be tightening.

Yet, only a few days later, the tone of the conversation, and the BoE’s actual actions changed dramatically. As reported by CNBC on September 28, 2022:

As of Wednesday, the bank will begin temporary purchases of long-dated U.K. government bonds in order to “restore orderly market conditions,” and said these will be carried out “on whatever scale necessary” to soothe markets.

CNBC

Over those few short days, the BoE completely reversed course. Their policy changed from reducing their bond holdings and raising interest rates as much as needed, to the exact opposite. A policy of unrestrained bond buying on whatever scale is necessary.

The exact severity of the current U.K. bond market gyrations is not fully understood at this time. However, there is at least some reason to believe that it is a threat. First, it was serious enough that the BoE stepped in to intervene. And intervene in a manner directly opposite to what they stated their intentions were only a few days earlier. Second, at least one observer makes particular note of the potential inability for the government of the U.K. to fund their operations through bond sales. From the same CNBC article as cited above, Antoine Bouvet, senior rate strategist at ING, states:

Bouvet told CNBC immediately after the announcement that the bank’s first priority for now had to be the functioning of the gilt market, suggesting the worst outcome would be for the sovereign to be left without market access and unable to secure financing.

CNBC

The thought of the Fed having to step in because the government is unable to sell its bonds, may sound absurd to many. But, consider the recent panic in the U.K. The U.K. is a prosperous country where its central bank very clearly stated their intent to fight inflation by selling bonds. Yet within days, they found it necessary to reverse course and do exactly the opposite. The current U.K. bond panic should serve as a warning. The risk of a similar occurrence within the United States is likely not as remote as would be preferred.

The banking industry’s need for liquidity (reserves) can constrain the Fed’s ability to tighten via balance sheet reduction

The Federal Reserve would almost certainly discontinue tightening to support the banking system as needed. The Fed has essentially guaranteed that the banking system will be provided sufficient reserves. Ample Reserve Regime: Great, How Did We Get Here & Why?, explains the guarantee that the Fed has made to the banking industry. In short, at the point when the banking system runs below the Fed’s interpretation of ample reserves, the Fed will make additional reserves available to the banking system. Measuring this arbitrary point may be difficult, but one thing is clear. The Fed intends to provide additional reserves if the banking system runs low. There are a number of ways for the Fed to supply additional reserves. All of them run counter to a policy of tightening.

The alternative, under current Fed policy, is to run the banking system low on reserves. This could result in banks not having sufficient funds to satisfy customer withdrawals, or banks curtailing lending. Additionally, banks may sell relatively liquid investments (like US treasuries) to raise additional cash to cover withdrawals. The first two possible outcomes would be rather unappealing to the economy as a whole. Banks selling treasuries would exasperate the risk that the Fed must step in to purchase treasuries to fund the government.

Banks and the Fed, it gets complicated

Projecting when the Fed pivots from its tightening stance to support the banking system’s liquidity is likely impossible. The Fed itself repeatedly admits that they do not know exactly how much reserves constitute “ample reserves.” Ample Reserve Regime: Great, How Did We Get Here & Why?, lists many of these instances of uncertainty. The Banking Dashboard page tracks a number of metrics to help visualize the risk levels and liquidity of the banking system.

Timing aside, it is likely that the Fed will need to provide reserves to the banking system. The US banking system has a track record of cratering a number of times over its history. [Coming Soon: Risky Banks – A History of Failure].

Now the Fed has removed the Reserve Requirements (Reserve Requirement Abolished! What Is the Fed Doing Now?) By doing so, any regulatory requirement for banks to hold sufficient reserves has also been removed. These actions increase the likelihood of a future failure (without intervention). In other words, this risk is beyond historical precedent in the United States. The Fed can, of course, step in and supply more liquidity in a number of different ways. That action may stem the severity of the problem. However, by doing so, the Fed would have reversed course and begun loosening monetary policy.

Get New Articles and News Straight to Your Inbox

The Fed’s ability to tighten is Constrained in How Much They Can Raise Interest Rates Before Fed Losses Mount Too Quickly

Framework and income

The Fed pays banks interest on deposits and reverse repos. The Fed earns interest on their treasury and mortgage-backed securities. Normally, the interest that the Fed earns is significantly greater than the interest that they pay. Now, there is a problem. The Fed purchased most of its assets in the past at lower rates, when rates were lower. But rates on bank deposits and reverse repos adjust almost immediately. Now the Fed is Losing Money.

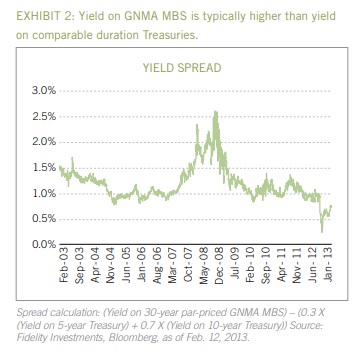

From Q4 2020 through Q1 2022, the Federal Government was paying a weighted interest rate of approximately 1.8% on the debt securities that they had issued. [See: Federal Government Data page]. Assuming the Fed held approximately the same portfolio of treasuries, they would be receiving roughly 1.8% in interest on it. Mortgage backed securities (MBS) yield a little bit more than treasuries, averaging around 1% more.

From this, one can estimate that the Fed is receiving around 2.8% on their MBS portfolio. As of October 5, 2022, the Fed held approximately $5.634 trillion in treasuries (Federal Reserve) and $2.98 trillion in MBS (Federal Reserve). At these interest rates, the Fed would receive approximately $8.451 billion in earned interest from the treasuries. And they would receive approximately $6.295 billion in earned interest from MBS per month. For a total of around $14.75 billion in interest earned per month.

Interest expenses

As mentioned above, the interest earned on the Fed’s treasuries and MBS will change over time. But this occurs slowly only as new security purchases replace maturing securities at the current rates. In contrast, what the Fed pays on deposits and reverse repos changes almost immediately in response to interest rates. This is because they are short-duration instruments that mature within days. At the time of this writing, the Fed is paying interest on Reserve Balances (Deposits held at the Fed) at a rate of 3.15% (Federal Reserve).

As of October 5, 2022, there were about $3.916 trillion dollars deposited at the Fed (Federal Reserve). This would result in approximately $10.28 billion in interest paid by the Fed per month on deposits.

In addition to the deposits that the Fed pays interest on, they also pay interest on the reverse repos. As of October 5, 2022, there were about $2.545 trillion of these repos for which the Fed owed interest payments (Federal Reserve). As of October 5, 2022, the rate on the reverse repo agreements was set at 3.05% (Federal Reserve). This is the maximum rate that can be reduced via bid. So, we will round the amount paid to an even 3.0% for the purposes of this calculation.

Fed – negative net interest income

At this interest rate and balance, the Fed would owe approximately $6.36 billion per month on reverse repos. This is a total of approximately $16.64 billion in interest payments that the Fed owes per month. Which is almost $2 billion a month greater than the approximately $14.75 billion that the Fed earns on its holdings. In other words, they are likely to have a net interest income loss of almost $2 billion per month.

Assuming interest rates continue to rise, the Fed’s position essentially guarantees growing net interest income losses. Interest paid will increase immediately with each rate hike. But the interest earned on the long-term holdings will remain relatively stable.

At this time, the Fed has a positive equity position. Additionally, it charges for some of its services. But it is concerning to see the Federal Reserve bank operating with negative net interest income. As it is to see them positioned for even greater losses as rates rise.

The Fed can lose money by selling bonds – another constraint to the Fed’s ability to tighten

The Fed is also constrained in how long they can tighten via balance sheet reduction. This situation exists because the Fed acquired the bulk of their bonds when interest rates were significantly lower. Interest rates are higher than the coupon rate on the bonds that the Fed holds. As a result, the bonds they hold would sell at a discount to their face value.

A current 10 year bond pays about 3.9% (at the time of this writing). This is more attractive than a bond that the Fed holds that likely yields closer to 2.0%. A bond with a 2.0% coupon paying interest semi-annually with 10 years remaining should sell for about $843.91 in today’s market when rates are approximately 3.9%.

See it Calculated for yourself

Input the following to see the above calculation, or experiment with your own numbers.

- Face value = $1000

- Annual Percent = 2%

- Frequency = Semi-annually

- Years to Maturity = 10

- Yield to Maturity = 3.9%

As a result, the Fed would lose about 15.61% on the sale of such a bond. The Fed would lose a higher percentage on sales of longer-term bonds and a lower percentage on the sales of shorter-term bonds. As of October 12, 2022, the Fed had $41.871 billion of equity. However, private banks’ paid in capital accounts for $35.086 billion of this equity. This means that the Fed had $6.785 billion of surplus capital. In other words, the Fed could lose as much as $6.785 billion without having more liabilities and paid in capital than they hold in assets (Federal Reserve). However, beyond the $6.785 billion in losses, the Fed would have more in obligations than they hold in assets. This calculation accounts for the banks’ paid in capital as an obligation rather than equity.

What is the Fed’s paid in capital account?

The Fed’s paid in capital, represents preferred shares owned by private member banks. The Fed requires these banks to invest in the Fed branch banks to utilize their services. Total paid in capital adjusts up and down based upon the number of financial institutions required to own preferred shares of the Fed. As well as the size of these banks’ capital stock (Federal Reserve).

If the capital stock of a bank decreases, the bank surrenders some of the shares back to the Fed. In such a case, the law requires the Fed to pay the bank for those shares. As such, a deficiency in this account could create significant problems. If there is a deficiency in this account, the Fed could potentially be required to return capital that it does not have. For this reason, a loss of $6.785 billion is the most the Fed can sustain before owing (liabilities + paid in capital for the purposes of this calculation) more than it owns.

A typical enterprise that owes more than it owns is likely to result in bankruptcy. Since the Fed can create more money at will, they would likely bail themselves out in some manner. However, by doing so, the Fed will have pivoted from a tightening stance to a stance of loosening monetary policy through the creation of more money.

How much of their treasury portfolio can the Fed sell?

How much of their treasury holdings can the Fed liquidate through sales of bonds before consuming the $6.785 billion? At a loss of around 15.61% as calculated above on ten-year treasuries, the Fed can only sell about $44 billion in such treasuries before erasing their surplus capital account. This is only a small fraction of their $5.634 trillion portfolio of treasuries, less than one percent. They could increase what they could sell somewhat by selling shorter-duration bonds. But it would not take selling a very large percentage of the Fed’s treasury portfolio to wipe out the surplus capital account. This constrains the Fed significantly in their ability to tighten via bond sales.

The Fed does have the option to wait until a security matures and then not re-invest the proceeds. This would reduce their bond holdings. And they could do so without incurring a loss, since bonds mature at face value. This method, however, constrains the Fed’s ability to tighten to using those securities as they mature. Meaning that they could tighten no more rapidly than their portfolio is maturing. In other words, the Fed can use this method to tighten, but it strictly constrains the Fed to using maturing securities.

The Fed is missing their own tightening objectives

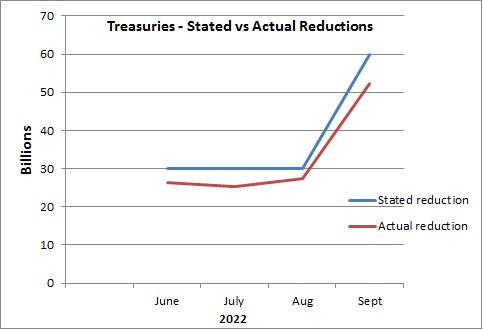

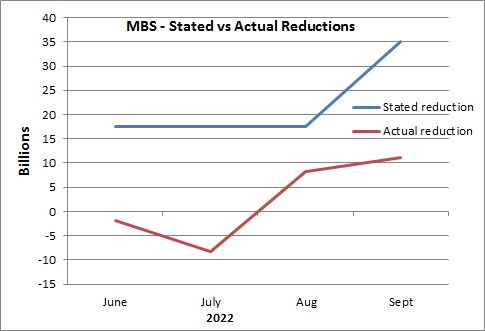

These conditions may explain why the Fed’s balance sheet reductions fall well below their stated pace (Federal Reserve). The Fed stated that balance sheet reductions were to begin in June. For the four months from the beginning of June through the beginning of October, the Fed has reduced only about 87.5% of the treasuries that they stated they would. More dramatically, the Fed only reduced about 10.6% of the mortgage-backed securities as they stated they would. (percentages are calculated from stated tightening cited above and Federal Reserve Data page). Clearly, they are not tightening as stated. In fact, there was not a single month where the Fed tightened as much as they stated. This statement holds true for both treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. So far, that is eight misses out of eight opportunities. The degree of the miss is particularly striking for MBS.

Political considerations may limit the Fed in its ability to tighten monetary policy

The Fed will probably play nice with the banks

There are two political considerations that may play a role in the Fed’s actions and are worthy of consideration. Neither of these considerations likely constitutes a hard and absolute limit on the Fed’s ability to tighten. Yet, it would be remiss to neglect the discussion of political considerations altogether. First, the Fed has certain commitments to the banks that are required to invest in it. It pays preferred dividends back to the banks required to invest in them in years when it is profitable. Elimination of the payment of these dividends due to loss would not be popular with the banking industry. Neither would simply jeopardizing banks’ preferred dividends due to significant deterioration in the Fed’s equity position.

Likewise, a deterioration of the Fed’s equity position endangers redemption of preferred shares. Which illustrates another reason that a significant reduction in the Fed’s equity position would cause angst across the banking sector. These considerations suggest that the Fed would likely experience political pressure if losses exceeded their surplus capital of $6.785 billion. This suggests that the Fed will be reluctant to take losses in excess of this amount. Likewise, it suggests that they are unlikely to take on losses over a period of several years.

The Fed will probably play nice with the government

Second, the Fed remits its profits back to the US Treasury. These remittances are subject to a certain equity threshold that must be satisfied. As well as, preferred dividends having been paid to the investing banks. A reduction in this revenue stream will negatively affect the Federal Government’s financial position. This could lead to Congressional scrutiny as the missing money impacts the government. This reduction in money received by the Federal Government will lead to even greater debt. Which in turn will lead to yet more treasuries that must be sold.

The Fed is technically independent. But it seems unlikely that they are unaware of these issues or that they will ignore those concerns entirely. Taking actions that unsettle either of these powerful entities too much seems unlikely. The banking sector and the Federal Government are both powerful forces. The Fed is surely cognizant of these facts. There is likely some degree of constraint upon the Fed’s ability to tighten as a result of these political considerations.

The Fed has problems related to how much it can tighten. They are complex and compounding

Each of the mentioned constraints limits the potential effectiveness of monetary policy in fighting inflation on its own. These constraints also interact with each other in ways that become complex. Often in a manner where one factor leads to greater constraint in another factor.

For example, as interest rates rise, the portfolio of bonds that the Fed holds will continue to lose value. So, the Fed’s losses when selling bonds grows the higher interest rates go. An increase in interest rates will constrain the Fed’s ability to tighten by selling bonds even more than it is currently. Ironically, the Fed’s tightening via raising interest rates constrains the Fed’s ability to tighten via bond sales.

Additionally, increases in interest rates will drive up the interest rates on the bonds that the Federal Government sells. This means the Federal Government will have to sell even more bonds to finance the higher interest payments. As discussed above, there are many reasons to believe that the open market may not have the ability and desire to purchase all of these treasuries. As a result, it is more likely that the Fed will have to step in as a buyer of bonds. The higher rates climb, the more likely this becomes. So, here again, as the Fed tightens by raising interest rates, they may be constraining themselves in other ways. In this case, through balance sheet reduction.

If current interest rates continue to increase, this would further increase the Fed’s negative net interest income. Additionally, the negative interest income losses will reduce surplus capital available to absorb losses on any bond sales. Raising interest rates tightens the monetary supply. Yet here again the act of tightening via interest rates actually further constrains the Fed’s ability to tighten in other ways. In this case, through balance sheet reduction due to the loss via negative net interest income.

These contradictory impacts lead to questioning if the Fed should tighten primarily via interest rates. Especially, considering the costs to society as their loan expenses balloon.

A remaining hope and a closing window

To succeed in meeting their mandates of stable price levels and full employment, the Fed must tamp down inflation. The Fed must defeat the current abnormally costly inflation prior to any of the above-mentioned constraints becoming excessively limiting. The window of time to do this is relatively narrow from a historical perspective. The US last faced inflation similar to the level it is today during the 1970s and early 1980s. Inflation ramped up from about 2.5% in June of 1972 and eventually hit almost 15% in March of 1980. Between June of 1972 and June of 1983 (11 years), inflation moved well away from 2.5%. Rarely fell below 5%. And ran as high as almost 15%. For the reasons stated above, the Fed likely cannot combat inflation for 11 years this time.

Therefore, the Fed must be more effective in this fight than they were during the 1970s. The Fed has acted aggressively with interest rate hikes and has begun reducing their balance sheet to some degree. However, the Fed has not utilized one of their tools to tighten monetary policy. In fact, the Fed recently abandoned this tool. Shortly after the economic lockdowns, the Fed responded by eliminating the reserve requirements for banks. This action should stimulate lending.

The opportunity

Now, however, the problem is the opposite and the Fed is trying to reduce demand to stifle inflation. Re-instating the reserve requirement should slow lending. If re-instating the reserve requirement is not enough, then the Fed can raise the percent of reserves required. This can continue until banks become more cautious. This action would both help fight inflation and to help insure that banks remain appropriately liquid. The Fed’s limited ability to tighten via balance sheet reduction and interest rate increases suggests the use of an additional tool. The Fed would be prudent to re-establish the reserve requirements for banks immediately. [learn more: Ample Reserve Regime: Great, How Did We Get Here & Why?] In addition to this policy effectively combating inflation, it would increase the liquidity and security of the banking industry.

With this policy too, the time to easily implement it may be a closing window. Presently, banks have significant reserves (See: Banking Dashboard). However, as banks lend out those reserves, the banks would have a harder and harder time meeting the same reserve requirements. Further delay in re-establishing reserve requirements could be a costly mistake. Both from higher inflation and potentially bank failures.

Conclusion

Some people may argue that monetary losses do not constrain the Fed, since they can create more money. Econ-Intel will concede that the Fed could lose money, then simply “bail themselves out” by creating additional money. While this may look like a feasible solution, this article examines how long the Fed can tighten. If the Fed starts creating more money, they will no longer be tightening. The money supply would increase. The Fed’s ability to tighten ceases with a bail out of newly created money.

As discussed above, there are many constraints to the Fed’s continued tightening through balance sheet reduction and interest rates. One of these constraints is likely to flare up into existence. Possibly before long. The Fed may have a relatively limited amount of time (especially in a historical context). It may not take long for one of these issues to arise and create a strong incentive for the Fed to pivot.

If this pivot away from tightening occurs before inflation recedes, an era of essentially uncontrollable inflation could be in store. It is illogical to assume that the Fed could control a second round of inflation in the near-term. If they abandon the current fight due to one of the constraints discussed.

Hopefully, the Fed’s abandonment of the reserve requirement does not lead to uncontrollable inflation or a banking crisis. However, a more reasonable strategy, than hope alone, would be for the Fed to re-implement the reserve requirement. Then the Fed can raise the requirement slowly, as needed, crushing inflation. We could then return to normal economic times. This process of Fed tightening could be painful. But there is no reason to expect it to be any more painful than the effect of rising interest rates. Furthermore, certainty that the Fed can sustain the inflation battle until inflation’s defeat improves. Finally, utilizing reserve requirements would insulate against a banking crisis, since banks are required to hold significant reserves. These are benefits worth experiencing.

Alternatively, the Fed can continue raising rates and hope that inflation withers away before the Fed’s ability to tighten does. But this method risks a return to easing prior to the defeat of inflation. Which could put inflation on a one-way street higher – perhaps permanently.

Updates:

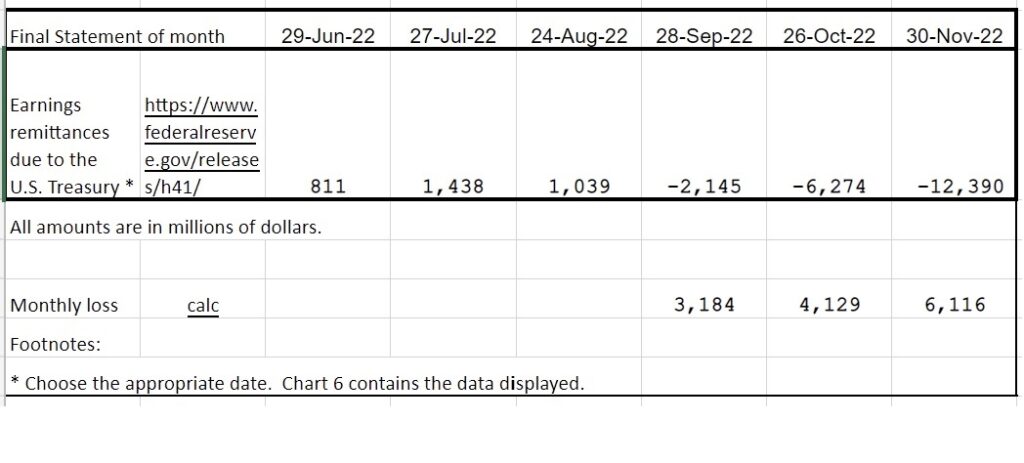

12/2/22 – Fed Losses Identified

Above we stated that the Fed could only raise interest rates so much without sustaining losses. Additionally, we stated that we suspected that the Fed had already begun losing money on a net interest margin basis. Here is data that shows that the Federal Reserve is indeed losing money.

Beginning in September, the accrued earnings due to the U.S. Treasury plunged negative, indicating that the Federal Reserve began losing money. Losses since that time have grown on a month by month basis. September’s loss was just over $3 billion, October exceeded $4 billion, and November rose above $6 billion. As warned about in the article above, this constrains how much the Fed can tighten.

See all News/Updates

Mind blown? If you learned something or found it interesting, you can easily share: